Wolves around Paris

The Wolves are in Paris

The Beast of Gâtinais (1652-1657)

From Versailles to Rambouillet: The Yveline Beast (1677-1683)

The Last Man-Eating Wolves (1687-1699)

Notes and References

Until recent times, there were wolf attacks in the areas around Paris. From the 15th century to the 17th century, wolves attacked in these zones, resulting in several dramatic episodes. Many attacks took place in the southern part of the Île-de-France: in the south of Yvelines, Seine-et-Marne, Essonne, and even as far as Eure-et-Loir and Loiret. Others took place in or on the edge of the capital itself. The large amounts of game kept by the aristocracy and the wealth of livestock destined for Parisian consumers, the significant forest cover, and the concentration of the long vulnerable rural population allowed the predator to survive.

The Wolves are in Paris

At the end of the Hundred Years’ War, with killings between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians, wolves came into Paris. In July 1421, they were so “starving” that they discovered an easy source of food: the bodies of recently buried people in villages and fields (see document 1). At night, scavenging wolves came into the “good towns”, and on several occasions, into the capital. In the summer of 1423, several wolves were captured within Paris, but the situation was at its worst from 1436 to 1440. In the Paris region, there were 60 to 80 victims, and in Valois, wolves came out of the forests to roam the countryside for months on end. In the summer of 1438, wolves came into Paris for a second time, strangling and eating several people. In his Chronique de Charles VII, Jehan Chartier emphasises that at the time, there “were so many wolves in the areas around Paris that it was astonishing, some of them ate people.” In December 1438, they came back down the Seine, snatching dogs and devouring a child not far from les Halles central market. In autumn 1439, they were in Paris for a fourth time, taking 14 victims in late September, and Parisians saw no relief until the killing of a “terrible and horrible wolf” called “Courtaut” (stump-tail, because it has lost its tail) in November. However, the next month, there was a fifth spate of attacks, possibly by rabid wolves.

When Louis XI came to the throne, wolves were still a threat in the Paris region. Everywhere, there were wolf hunts. In 1461, when the reconstruction of the Île-de-France had already begun, 227 wolves were officially killed in the viscounty of Paris, in barely six months: 157 healthy adults, a rabid female, 64 male cubs, and 5 female cubs.

This gives a good idea of the extent of wolf populations. They were helped by the abundance of small wooded areas: in the Séquigny forest (since destroyed) in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois, 5 wolves were killed. There were 22 killed in Bondy, 4 in Champrosay - on the edge of the Sénart forest - and 16 “around Montlhéry ”, in the wooded hills of Hurepoix. However, outside of wooded regions, the open-field plateaux were also affected: 8 wolves were killed in Gonesse and 11 nearby, 8 in Mitry, 3 in Châtenay-en-France, and 2 in Thiais. Around the capital, wolves were also present in the Longboyau plateau and the French plains. The same goes for the inner suburbs, with 6 wolves killed “around Chaillot”, 4 “around the justice of Paris” (the Gibbet of Montfaucon), 1 “around Saint-Germain-des-Prés”, in still-rural areas around the capital. Three centuries later, there were only 20 wolves killed on average in the years V and VI of the French Republican calendar. The yearly average went from 450 to around 20. Under Charles VII, the areas around Paris contained twenty to thirty times more wolves than at the end of the French Revolution. As an epilogue to these dark years, the end of the Wars a Religion left a trail of destruction, which brought wolves in its wake. In 1595, as observed by Pierre de l'Estoile in his memoirs, a wolf came into Paris to devour a child on Place de Grève: “a phenomenal thing, and a bad sign”!

Later, the threats abated. On 24 December 1692, as an influx of wolves spread terror through the Paris region, to the west of Montlhéry, a young girl of 15, Angélique Michaut, was bitten by a wolf at midnight mass in Villejuif. On the edge of Paris, there was widespread concern and over 1500 people called upon Saint Hubertus, in the hopes of avoiding the terrible illness. However, the victim died in Orly the following 4 February. After this episode. Wolves became a mere spectacle for Parisians. In November 1708, carriages still gathered in the Boulogne woods to see them being hunted. Louis of France came to hunt them for the last time, to the great delight of Parisian women.

Documents 1. 1421-1439.Gardez-vous de Courtaud ! Les loups sont entrés dans Paris.Source : Journal d'un bourgeois de Paris (1405-1449), éd. A. Tuetey, Paris, H. Champion, 1881. Juillet 1421 : « En ce temps [peu après la Saint-Martin d'été, 4 juillet] étaient les loups si affamés qu'ils déterraient à leurs pattes les corps des gens qu'on enterrait aux villages et aux champs ; car partout où on allait, on trouvait des morts aux champs aux villes de la grand pauvreté qu'ils souffraient par la maldite guerre qui toujours croissait de mal en pire » (p. 154). Fin juillet 1421 : « En ce temps, étaient les loups si affamés qu'ils entraient de nuit ès bonnes villes et faisaient moult et divers dommages, et souvent passaient la rivière de Seine et plusieurs autres à nu ; et aux cimetières qui étaient aux champs, aussitôt que l'on avait enterré les corps, ils venaient par nuit et les dévoraient et les mangeaient » (p. 156). Fin juillet/début août 1423 : « En ce temps, venaient à Paris les loups toutes les nuits, et en prenait-on souvent trois ou quatre à une fois, et étaient portés parmi Paris pendus par les pieds de derrière, et leur donnait-on de l'argent grand foison » (p. 187). Décembre 1438 : « En ce temps venaient les loups dedans Paris par la rivière et prenaient les chiens, et si mangèrent un enfant de nuit en la place aux Chats, derrière les Innocents » (p. 343). Septembre 1439 « En celui temps, spécialement tant comme roi fut à Paris, furent les loups si enragés de manger chair d'homme, de femme ou d'enfants que en la dernière semaine de septembre étranglèrent et mangèrent quatorze personnes, que grands que petits, entre Montmartre et la porte Saint-Antoine, que dedans les vignes que dedans les marais ; et s'ils trouvaient un troupeau de bêtes, ils assaillaient le berger et laissaient les bêtes... ». Novembre 1439 : « La vigile Saint-Martin [10 novembre] fut tant chassé un loup terrible et horrible que on disait que lui tout seul avait fait plus des douleurs devant dites que les autres ; celui jour fut pris et n'avait point de queue, et pour ce fut nommé Courtaut, et parlait autant de lui comme d'un larron de bois ou d'un cruel capitaine, et disait-on aux gens qui allaient aux champs : « Gardez-vous de Courtaut ! ». Icelui jour fut mis en une brouette, la gueule ouverte, et mené parmi Paris, et laissaient les gens toutes choses à faire, fut boire, fut manger, ou autre chose nécessaire que ce fut, pour aller voir Courtaut, et pour vrai, il leur valu plus de 10 francs la cueillette ». Décembre 1439 : « Le xvie jour de décembre, vinrent les loups soudainement et étranglèrent quatre femmes ménagères, et le vendredi ensuivant ils en affolèrent dix-sept entour Paris, dont il en mourut onze de leur morsure » (p. 348-349). |

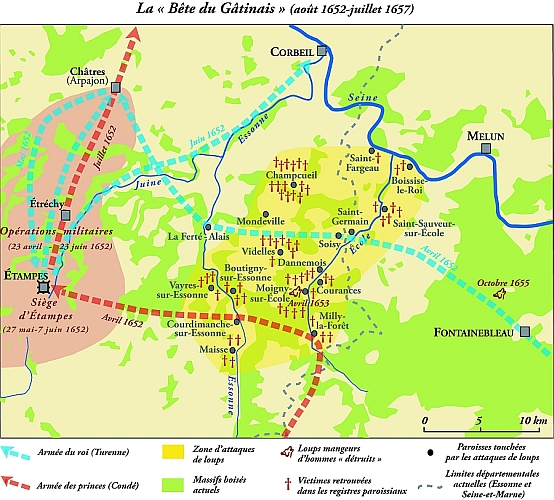

The Beast of Gâtinais (1652-1657)

In 1652, the operations in connection with the Princes’ Fronde wreaked havoc and caused bloodshed in campaigns in the south of Paris. After the siege of Étampes, the flats were strewn with unburied bodies. Typhus and epidemic illnesses filled the cemeteries. In this climate of insecurity, a few scavenging wolves developed a taste for human flesh. According to many witnesses, they came to attack the weakest among the living, in a poverty-stricken and helpless rural population (see document 2 - 1 and document 2 - 2). In around twenty villages in Gâtinais, between the Forest of Fontainebleau and the Hurepoix woods south-west of Paris, straddling the current departments of Essonne and Seine-et-Marne, fears peaked. There were many victims (see document 2 - 3).

Far from being confined to the last few months of 1652 (the “year of terror”), the attacks actually went on for five years. Several man-eating wolves were killed in succession. On 18 April 1653, when the attacks finally stopped after a “poisonous beast” in wolf form was killed, witnesses testified to the end of the tragedy. Among others, Jean Bareau stated that he:

- « ... vue ladite bête étant en forme de métir, qui avait le poil blond et le col blanc, se voulant jeter sur ledit Bereau pour le terrasser en venant de Milly audit Moigny, et est celle que l'on a tuée, après avoir vue et considéré il y a environ cinq à six semaines »

- “… saw the beast in question, in mongrel form, with blond fur and a white neck, attempting to pounce on this Bereau to bring him down, coming from Milly in Moigny, and this is the beast that was killed, after it was seen and observed five to six weeks ago.”

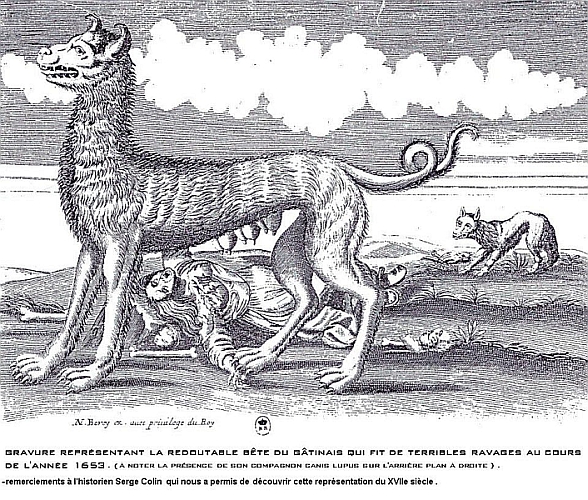

Later, the subject appeared in print, accompanied by a terrifying allegorical plate.

For the wolf which became the “Beast of Gâtinais”, the image is striking and the description effective. In the background is a vast desert, strewn with bones and remains of various ages and sizes. In the middle is an enormous animal, a scraggy female hybrid of a wolf, a bear, and a lion, described as a “horrible monster”. With its steely claws, it has just torn open a dead woman’s chest and decapitated her child. The patchy hair, clutching hands, and dishevelled clothing of the unfortunate victim indicate a long fight, but the victor is there, with one paw on the dead body, whilst in the background, an animal more easily identifiable as a wolf also stands triumphantly on the battlefield. Other similar beasts followed on from this. On 16 October 1655, France’s great wolf hunter, Montmorin, Marquis of Saint-Hérem, was considered a saviour when he killed “this evil beast”. However, another followed, because victims were still being found into July 1657.

In the history of the “ferocious beasts” that long haunted rural minds, the Beast of Gâtinais was the first to give rise to significant documentation (see document 2 - 4). Today, we have data for 58 victims of this beast, found in parish registers (see document 2 - 5).

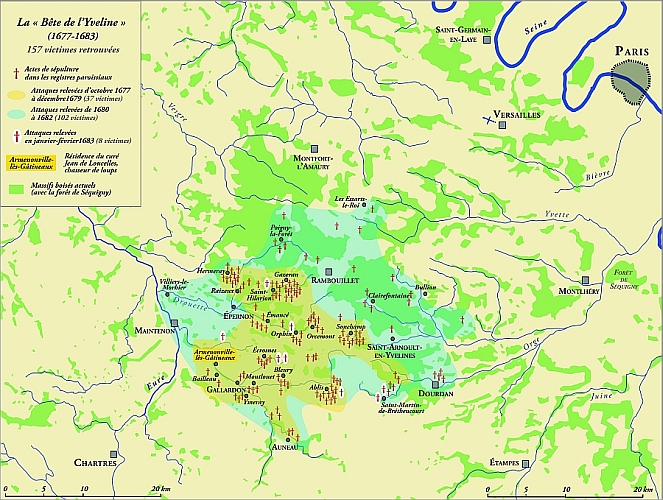

From Versailles to Rambouillet: The Yveline Beast (1677-1683)

From October 1677 to February 1683, over more than five years, terror reigned over the south-west of the Île-de-France. Just outside Versailles, the new capital completed under Louis XIV, women and children were devoured by “kinds of wolves” which ventured into towns. Almost 200 people were killed in dramatic circumstances, and many more were injured to varying degrees (see document 3). Records of 157 victims have been found and included in the database. Despite the action of the louveterie wolf hunters and hunts organized locally, the “beast” remained at large. On 23 September 1682, passing through Chartres for the occasion of the Duc de Bourgogne’s birth, the king discovered the extent of the tragedy and granted 900 French livres to victims’ families.

Document 3. 190 actes de sépulture présentés à Louis XIVSource : Archives communales de Bailleau-Armenonville, Inventaire des titres de l'église d'Armenonville-les-Gâtineaux (1638-1840) « Nous devons faire mention de la désolation que causèrent 8 ou 10 lieues à la ronde une quantité de loups accoutumés à manger de la chair humaine depuis l'année 1680 jusqu'en 85. Comme ce fléau commença après que notre invincible monarque Louis le Grand eut donné la paix à tous ses ennemis, ennuyé qu'il était de vaincre, il est à supposer que ces misérables bêtes qui s'attaquaient plutôt aux hommes qu'aux bestiaux avaient suivi les armées et que s'étant nourries de soldats morts dans les combats, elles ne voulaient plus d'autre nourriture que de chair humaine, et dès lors on peut dire sans exagération que ces loups carnassiers dévorèrent plus de 500 personnes, mais beaucoup plus de femmes et d'enfants que d'hommes parce que, pour peu qu'on se défendît, ils se retiraient ; ce qui sauva la vie à une grande quantité d'hommes et même de femmes et d'enfants qui, ne sortant jamais de chez eux sans se munir de quelques ferrements avaient le courage de leur résister, et ce qui fit qu'il y en eut un très grand nombre de blessés. Dont Sa Majesté fut touchée lorsqu'elle vint à Chartres en action de grâce de l'heureux accouchement de Madame la Dauphine et de la naissance de Mr le duc de Bourgogne, car ayant eu l'honneur d'être choisi pour faire une recherche seulement à 3 lieues des environs d'Armenonville, l'on présenta au roi les extraits d'enterrements d'ossements de 190 sans y comprendre les blessés, auxquels S. M. fit distribuer une somme de 900 livres, et en même temps ordonna au grand maître de sa louveterie de faire incessamment chasser pour détruire ces désolantes bêtes, ce qui ne peut être fini que longtemps après. Les bonnes gens voulaient que ce fussent des sorciers, soit parce qu'elles attaquaient et dévoraient des personnes à divers endroits au même jour, soit parce que souvent elles s'échappaient des embuscades qu'on leur faisait et passaient au milieu des personnes qu'on postait autour des bois sans qu'on osât les tirer, parce que la peur faisait souvent tomber les armes de la main à bien des gens inusités à les porter. J'assistai, avec Mr Bruneau, curé de Villiers [le-Morhier], à la prise d'un, que je fis poursuivre par les habitants de Gallardon et les miens dans la vallée qui est entre eux et nous, pour s'être voulu jeter sur un particulier ; et comme cet animal se vit fortement poussé par les taillis de cette vallée, il fut obligé d'en sortir pour gagner le petit bois de Herleville, où ce que nous étions de gens à cheval le poursuivîmes vigoureusement, et plus que personne ledit curé de Villiers qui, étant avantageusement monté, mais sans autres armes que son bâton ferré et l'ayant joint avant qu'il fut parvenu audit bois, lui enfonça heureusement sur le milieu du dos ; de quoi cet animal se sentant mortellement blessé se l'arracha et le grugea en deux ; après quoi, tout hérissé et écumant de rage, faisant ses efforts pour gagner ledit taillis, le sieur curé descendant de cheval, et prenant le reste de son bâton lui relança une seconde fois avec un pareil succès, dont son pas fut tout à fait modéré, et le sieur Delacroix, bourgeois de Gallardon, l'ayant devancé, lui tira un coup de fusil qui le mit à bas. » |

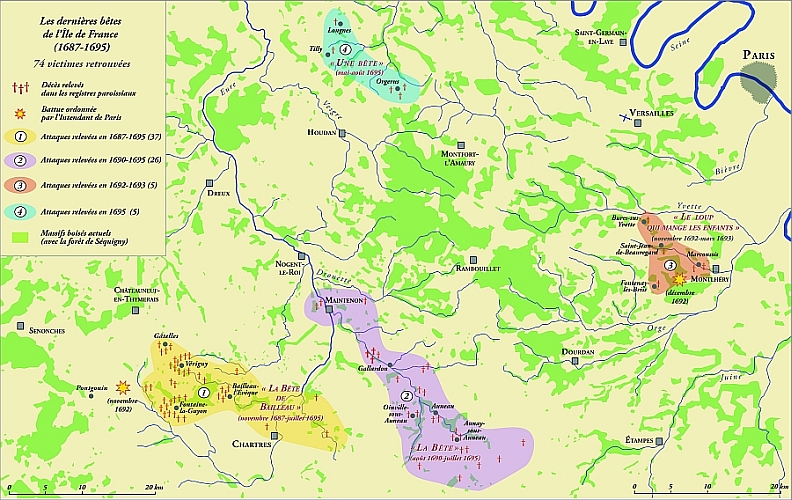

The Last Man-Eating Wolves (1687-1699)

Until the end of the 17th century, the wolf presence intermittently threatened populations to the south of the Île-de-France. From 1687 to 1695, in the north west of Chartres, there was a spate of attacks on humans. A “ferocious beast” of “unknown species” terrorized Gâtine and Thymerais. Villages were struck by tragic deaths, including children (12 incidents) as ever, but also adolescents (7 girls aged 15 to 19) and, more unusually, adults (1 man and 17 women aged 20 to 60). The range of victims attacked by the predator indicates an unusual kind of behaviour among man-eating wolves. The Bailleau-l'Évêque woods lay at the heart of the wolf’s incursions. It quickly became known to locals as the “Beast of Bailleau”. On 18 March 1694, this was the name used when it came to the edge of Chartres, in the Saint-Maurice suburb, tearing out the throat of Lubine Pelletier, 40, a carter’s wife

At this time, another area was being terrorized by wolf attacks. Once again striking in the Auneau and Gallardon region, to the south of the Yveline forest, “the beast” more typically took children (all 37 of the deaths between 1690 and 1695). For a short time, the danger came near the capital, because on 1 December 1692, the Paris intendant received the order to conduct hunts around Montlhéry, to “kill the wolf that eats children”. On 29 October 1692 (Fontenay-lès-Briis) and on 9 March 1693 (Bures-sur-Yvette), the villages of Hurepoix next to the eastern edge of the Yveline forest were in a state of alert. Several young women guarding cows were taken and only their heads were found, for example Marie Mignet in Saint-Jean-de-Beauregard (see document 4). The predatory animals (two “wild beasts” in Bures) were particularly voracious, leaving very little remains of any of the bodies for burial. Again, this suggests unusual behaviour on the part of the wolves in question.

Documents 4. De simples têtes à enterrerSource : Arch. dép. Essonne, état civil, registre de Saint-Jean-de-Beauregard, BMS 1692-1751 vue 4. « Ce jourd'hui 3e jour du mois de février 1693 a été inhumé dans le cimetière de cette paroisse une partie de la tête de Marie Mignet, qui a été trouvée dans les dans les bois de Marcoussis où elle a été dévorée par les loups en gardant les vaches le premier jour dudit mois, âgée de 11 ans ou environ, fille légitime de Jean Mignet et de défunte Claude Laurens. »

Source : Arch. dép. Essonne, état civil, registre de Bures-sur-Yvette BMS 1688-1714 vue 111. « L'an de grâce 1693, le mardi 10e jour du mois de mars, a été inhumé dans la nef de l'église de cette paroisse de Bures, la teste d'Élisabeth Boëte, avec une côte et quelques boyaux ou intestins, âgée de 8 ans ou environ, fille de Thomas Boëte, le r este du corps ayant été mangé par deux bêtes fauves dans les bois de Montjay, paroisse dudit Bures, le lundi 9e jour dudit mois. » |

An End to the Proliferation of Wolves: The Grand Dauphin’s Hunts

Until he start of the 18th century, wolves were heavily present around Paris. Striking proof of this was provided by the Bourbons, with their many hunt days, particularly Louis XIII, followed by Louis of France (the Grand Dauphin) at the end of the 17th century.

Louis XIII: Wolf Hunter around Paris

In 1610, four months after his father died, the young Louis XIII had his puppies chase two wolf cubs in the Tuileries on 23 September. He was still just 9 years old. Just north of Paris, the French plain had a high wolf population. A decade on, they attracted the monarch’s attention. He had become an unrivalled knight and a tireless hunter. On 11 March 1623, Louis XIII hunted wolves in Plessis-au-Bois (Seine-et-Marne) in the morning, then around Louvres-en-Parisis (Val-d’Oise) in the afternoon. He hunted again the next day. On 26 March 1624, after hunting two stags, the king hunted wolves, running two of them before ending the day with a fox hunt! On 8 April, he hunted in Moussy-le-Neuf (Val-d’Oise). From the Goële woods to the Valois forests, there were frequent wolf hunts across France’s vast plain, with its cereal fields north of Paris,2 as well as in Beauce. On 25 September 1627, after recovering from an illness, the monarch took an “exceptionally large” wolf in Janville. The next day, he was hunting wolf and fox again, before heading to The Loire Valley then la Rochelle.3 A year after the taking of the Protestant city, an attack of “gout” did not prevent him hunting wolves on 25 November 1629 in Livry, just outside Paris. In Saint-Maur, the king took the queen hunting and took five wolves on 12 September 1637. On 7 October 1640, he told Cardinal Richelieu of his strong desire to go hunting wolves, which were numerous around Meaux:

- « Je vous écris de billet pour savoir de vous s'il n'y a point d'affaires qui me puissent empêcher d'aller mardi à Monceaux, où il y a quatre ans que je n'ai été, où on me mande qu'il y a grande quantité de loups ; vous savez que j'aime bien fort cette chasse4. »

- “I am writing you this note to ask you whether there is any business that might prevent me from going to Monceaux on Tuesday. I have not been there for four years, and I am told there are many wolves there; you know how much I like to hunt wolves.”

Louis of France, the Grand Dauphin: Record Wolf-Hunter

After Louis XIII, the wolf population was still dense. One of the best illustrations of this is the hunting success of Louis of France, the Grand Dauphin (Louis XIV’s son). From 12 July 1684 to 16 January 1711, he conducted 1027 wolf hunts, recorded by the Marquis of Dangeau in his Journal. Excluding Chambord, where he went just five times in 1684 and 1685, all of his hunting activities were focussed in Île-de-France. Of these 1022 days (or half-days) hunting wolves, 61 were fruitless: no wolves were “chased” or “found”. However, the others were successful, with several wolves taken on some occasions: six on 10 November 1684 and two on 24 October 1687 in Fontainebleau.

The total number of wolves killed (around a thousand) is even more impressive considering that they were all adults and that Louis had many other obligations during these twenty-six years. A person of his status had many demands on his time: military campaigns on the Northern frontiers, the need to be at the king’s side for major festivals and his preferred stag or boar hunts, as well as occasional health problems or frosts too severe for the hunt to go out. In 1686, a year which Louis was able to devote as much time as possible to “entertainment”, he went out 101 times, and returned victorious every time. Looking at the geographical distribution of all his hunts, we can observe that 78% of them (786/1022) took place all or in part less than 25km from the centre of Paris (table 1).

Table 1.

Les loups autour de Paris à la fin du xviie siècle

Répartition des 1 022 chasses du Grand Dauphin (1684-1711)

Source : Journal du marquis de Dangeau

| Lieu |

Nombre de chasses |

Distance/Notre-Dame (en km) |

| Anet (forêt de Dreux) |

14 |

65 |

| Bois de Boulogne |

5 |

7,5 |

| Rueil (Buzenval) |

1 |

8 |

| Chantilly |

2 |

37 |

| Compiègne |

6 |

65 |

| Vaux-de-Cernay (Les) |

4 |

37 |

| Fontainebleau (forêt) |

181 |

57 |

| Poissy (bois de l'Authie) |

7 |

30 |

| Lévis-Saint-Nom |

1 |

30 |

| Livry (forêt de Bondy) |

20 |

15 |

| Maintenon |

1 |

62 |

| Marcoussis |

2 |

25 |

| Marly-le-Roi (environs) |

132 |

21 |

| Meudon |

35 |

9 |

| Montmorency |

4 |

18 |

| Montfort-l'Amaury |

5 |

40 |

| Rambouillet |

2 |

45 |

| Saint-Germain-en-Laye |

57 |

21 |

| Saint-Léger-en-Yvelines |

3 |

44 |

| Saint-Maur-des-Fossés |

1 |

14 |

| Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois

|

3 |

25 |

| Sénart (forêt) |

106 |

24 |

| Trappes |

1 |

25 |

| Verrières-le-Buisson |

12 |

13 |

| Versailles (environs) |

417 |

20 |

The location of the royal residences favoured such a high concentration: he went out 417 times from Versailles, 12 times from Marly, and at least 35 more from his Meudon castle (because the Marquis of Dangeau often says little or nothing about these hunts). However, the Grand Dauphin did not hesitate to request the hospitality of several important people, in order to access other hunting sites such as the forests of Sénart or Livry, where there were many wolves. They came right to the edge of the capital: the Grand Dauphin hunted them five times in the Boulogne woods. In the last years of his life, when he went “hunting” in the woods, his trips provoked great interest. On 9 November 1708, “many Parisian women came to see the hunt, which was very beautiful.” Three days later, he left Meudon again, returning to the Boulogne woods to flush out “a wolf which was lingering there.” Keen not to miss the show, carriages came from all around. Then, at the start of the 18th century, there were no longer many wolves around Paris. It is true that the passion of a hunter like the Grand Dauphin contributed to this fall in numbers: in the last ten years of his activity, there were even 32 fruitless expeditions (twice as many as before 1700). Compared to the 1680s, when there were so many wolves, this was a significant drop. It was so obvious that in January 1688, the Mercure de France wrote that:

“In France, all wild animals are taken for wolves. There are now hardly any around Paris: Monseigneur le Dauphin has purged the area of them.”

However, they spoke too soon. Around Paris, the Grand Dauphin’s hunts were not enough to eradicate wolves. The animals benefitted from a fall in hunting pressure caused by his absences from May to October, over five successive years from 1690 to 1694, to take part in the War of the League of Augsburg on the Northern front. He only went wolf-hunting around twenty times a year during this period, cutting his activities by half. Thus, despite the relative increase in unsuccessful hunts (which can basically be taken to indicate a fall in numbers), wolves had not left the Île-de-France when Louis was killed by his worst enemy, on 14 April 1711 in his Château de Meudon (table 2).

Table 2.

Un indicateur relatif de la régression des loups autour de Paris :

Les chasses infructueuses du Grand Dauphin

Source : Journal de Dangeau

| Période |

Ensemble des chasses (1) |

Chasses heureuses |

Chasses infructueuses (3) |

(3)/(1) |

| 1685-1689 |

287 |

280 |

7 |

2,4 % |

| 1690-1694 |

113 |

105 |

8 |

7 % |

| 1695-1699 |

193 |

183 |

10 |

5,2 % |

| 1700-1704 |

236 |

212 |

24 |

10,2 % |

| 1705-1709 |

126 |

118 |

8 |

6,8 % |